| Cycle Type | Fixed Points | Longest Cycle | Count | Probability | Cum Count | Cum Prob |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | 0 | 12 | 39,916,800 | 0.08333 | 479,001,600 | 1.00000 |

| 11|1 | 1 | 11 | 43,545,600 | 0.09091 | 439,084,800 | 0.91667 |

| 10|2 | 0 | 10 | 23,950,080 | 0.05000 | 395,539,200 | 0.82576 |

| 10|1|1 | 2 | 10 | 23,950,080 | 0.05000 | 371,589,120 | 0.77576 |

| 9|3 | 0 | 9 | 17,740,800 | 0.03704 | 347,639,040 | 0.72576 |

| 9|2|1 | 1 | 9 | 26,611,200 | 0.05556 | 329,898,240 | 0.68872 |

| 9|1|1|1 | 3 | 9 | 8,870,400 | 0.01852 | 303,287,040 | 0.63316 |

| 8|4 | 0 | 8 | 14,968,800 | 0.03125 | 294,416,640 | 0.61465 |

| 8|3|1 | 1 | 8 | 19,958,400 | 0.04167 | 279,447,840 | 0.58340 |

| 8|2|2 | 0 | 8 | 7,484,400 | 0.01562 | 259,489,440 | 0.54173 |

| 8|2|1|1 | 2 | 8 | 14,968,800 | 0.03125 | 252,005,040 | 0.52610 |

| 8|1|1|1|1 | 4 | 8 | 2,494,800 | 0.00521 | 237,036,240 | 0.49485 |

| 7|5 | 0 | 7 | 13,685,760 | 0.02857 | 234,541,440 | 0.48965 |

| 7|4|1 | 1 | 7 | 17,107,200 | 0.03571 | 220,855,680 | 0.46108 |

| 7|3|2 | 0 | 7 | 11,404,800 | 0.02381 | 203,748,480 | 0.42536 |

| 7|3|1|1 | 2 | 7 | 11,404,800 | 0.02381 | 192,343,680 | 0.40155 |

| 7|2|2|1 | 1 | 7 | 8,553,600 | 0.01786 | 180,938,880 | 0.37774 |

| 7|2|1|1|1 | 3 | 7 | 5,702,400 | 0.01190 | 172,385,280 | 0.35988 |

| 7|1|1|1|1|1 | 5 | 7 | 570,240 | 0.00119 | 166,682,880 | 0.34798 |

| 6|6 | 0 | 6 | 6,652,800 | 0.01389 | 166,112,640 | 0.34679 |

| 6|5|1 | 1 | 6 | 15,966,720 | 0.03333 | 159,459,840 | 0.33290 |

| 6|4|2 | 0 | 6 | 9,979,200 | 0.02083 | 143,493,120 | 0.29957 |

| 6|4|1|1 | 2 | 6 | 9,979,200 | 0.02083 | 133,513,920 | 0.27873 |

| 6|3|3 | 0 | 6 | 4,435,200 | 0.00926 | 123,534,720 | 0.25790 |

| 6|3|2|1 | 1 | 6 | 13,305,600 | 0.02778 | 119,099,520 | 0.24864 |

| 6|3|1|1|1 | 3 | 6 | 4,435,200 | 0.00926 | 105,793,920 | 0.22086 |

| 6|2|2|2 | 0 | 6 | 1,663,200 | 0.00347 | 101,358,720 | 0.21160 |

| 6|2|2|1|1 | 2 | 6 | 4,989,600 | 0.01042 | 99,695,520 | 0.20813 |

| 6|2|1|1|1|1 | 4 | 6 | 1,663,200 | 0.00347 | 94,705,920 | 0.19772 |

| 6|1|1|1|1|1|1 | 6 | 6 | 110,880 | 231.481u | 93,042,720 | 0.19424 |

| 5|5|2 | 0 | 5 | 4,790,016 | 0.01000 | 92,931,840 | 0.19401 |

| 5|5|1|1 | 2 | 5 | 4,790,016 | 0.01000 | 88,141,824 | 0.18401 |

| 5|4|3 | 0 | 5 | 7,983,360 | 0.01667 | 83,351,808 | 0.17401 |

| 5|4|2|1 | 1 | 5 | 11,975,040 | 0.02500 | 75,368,448 | 0.15734 |

| 5|4|1|1|1 | 3 | 5 | 3,991,680 | 0.00833 | 63,393,408 | 0.13234 |

| 5|3|3|1 | 1 | 5 | 5,322,240 | 0.01111 | 59,401,728 | 0.12401 |

| 5|3|2|2 | 0 | 5 | 3,991,680 | 0.00833 | 54,079,488 | 0.11290 |

| 5|3|2|1|1 | 2 | 5 | 7,983,360 | 0.01667 | 50,087,808 | 0.10457 |

| 5|3|1|1|1|1 | 4 | 5 | 1,330,560 | 0.00278 | 42,104,448 | 0.08790 |

| 5|2|2|2|1 | 1 | 5 | 1,995,840 | 0.00417 | 40,773,888 | 0.08512 |

| 5|2|2|1|1|1 | 3 | 5 | 1,995,840 | 0.00417 | 38,778,048 | 0.08096 |

| 5|2|1|1|1|1|1 | 5 | 5 | 399,168 | 833.333u | 36,782,208 | 0.07679 |

| 5|1|1|1|1|1|1|1 | 7 | 5 | 19,008 | 39.683u | 36,383,040 | 0.07596 |

| 4|4|4 | 0 | 4 | 1,247,400 | 0.00260 | 36,364,032 | 0.07592 |

| 4|4|3|1 | 1 | 4 | 4,989,600 | 0.01042 | 35,116,632 | 0.07331 |

| 4|4|2|2 | 0 | 4 | 1,871,100 | 0.00391 | 30,127,032 | 0.06290 |

| 4|4|2|1|1 | 2 | 4 | 3,742,200 | 0.00781 | 28,255,932 | 0.05899 |

| 4|4|1|1|1|1 | 4 | 4 | 623,700 | 0.00130 | 24,513,732 | 0.05118 |

| 4|3|3|2 | 0 | 4 | 3,326,400 | 0.00694 | 23,890,032 | 0.04987 |

| 4|3|3|1|1 | 2 | 4 | 3,326,400 | 0.00694 | 20,563,632 | 0.04293 |

| 4|3|2|2|1 | 1 | 4 | 4,989,600 | 0.01042 | 17,237,232 | 0.03599 |

| 4|3|2|1|1|1 | 3 | 4 | 3,326,400 | 0.00694 | 12,247,632 | 0.02557 |

| 4|3|1|1|1|1|1 | 5 | 4 | 332,640 | 694.444u | 8,921,232 | 0.01862 |

| 4|2|2|2|2 | 0 | 4 | 311,850 | 651.042u | 8,588,592 | 0.01793 |

| 4|2|2|2|1|1 | 2 | 4 | 1,247,400 | 0.00260 | 8,276,742 | 0.01728 |

| 4|2|2|1|1|1|1 | 4 | 4 | 623,700 | 0.00130 | 7,029,342 | 0.01467 |

| 4|2|1|1|1|1|1|1 | 6 | 4 | 83,160 | 173.611u | 6,405,642 | 0.01337 |

| 4|1|1|1|1|1|1|1|1 | 8 | 4 | 2,970 | 6.200u | 6,322,482 | 0.01320 |

| 3|3|3|3 | 0 | 3 | 246,400 | 514.403u | 6,319,512 | 0.01319 |

| 3|3|3|2|1 | 1 | 3 | 1,478,400 | 0.00309 | 6,073,112 | 0.01268 |

| 3|3|3|1|1|1 | 3 | 3 | 492,800 | 0.00103 | 4,594,712 | 0.00959 |

| 3|3|2|2|2 | 0 | 3 | 554,400 | 0.00116 | 4,101,912 | 0.00856 |

| 3|3|2|2|1|1 | 2 | 3 | 1,663,200 | 0.00347 | 3,547,512 | 0.00741 |

| 3|3|2|1|1|1|1 | 4 | 3 | 554,400 | 0.00116 | 1,884,312 | 0.00393 |

| 3|3|1|1|1|1|1|1 | 6 | 3 | 36,960 | 77.160u | 1,329,912 | 0.00278 |

| 3|2|2|2|2|1 | 1 | 3 | 415,800 | 868.056u | 1,292,952 | 0.00270 |

| 3|2|2|2|1|1|1 | 3 | 3 | 554,400 | 0.00116 | 877,152 | 0.00183 |

| 3|2|2|1|1|1|1|1 | 5 | 3 | 166,320 | 347.222u | 322,752 | 673.802u |

| 3|2|1|1|1|1|1|1|1 | 7 | 3 | 15,840 | 33.069u | 156,432 | 326.579u |

| 3|1|1|1|1|1|1|1|1|1 | 9 | 3 | 440 | 918.577n | 140,592 | 293.511u |

| 2|2|2|2|2|2 | 0 | 2 | 10,395 | 21.701u | 140,152 | 292.592u |

| 2|2|2|2|2|1|1 | 2 | 2 | 62,370 | 130.208u | 129,757 | 270.891u |

| 2|2|2|2|1|1|1|1 | 4 | 2 | 51,975 | 108.507u | 67,387 | 140.682u |

| 2|2|2|1|1|1|1|1|1 | 6 | 2 | 13,860 | 28.935u | 15,412 | 32.175u |

| 2|2|1|1|1|1|1|1|1|1 | 8 | 2 | 1,485 | 3.100u | 1,552 | 3.240u |

| 2|1|1|1|1|1|1|1|1|1|1 | 10 | 2 | 66 | 137.787n | 67 | 139.874n |

| 1|1|1|1|1|1|1|1|1|1|1|1 | 12 | 1 | 1 | 2.088n | 1 | 2.088n |

Permutations and the 100 Prisoner Problem

Permutations, Fixed Points, Cycle Types, and the 100 Prisoners Puzzle

This note collects a few connected facts about uniform random permutations in \(S_n\).

Fixed points

On average a random permutation has one fixed point!

Let \(\Pi\) be a uniformly random permutation of \({1,\dots,n}\). A fixed point is an \(i\) such that \(\Pi(i)=i\). Define indicator random variables \[ I_i := 1_{{\Pi(i)=i}},\qquad i=1,\dots,n, \] and let \[ F_n := \sum_{i=1}^n I_i \] be the number of fixed points.

For a fixed \(i\), all \(n\) values \(\Pi(i)\in\set{1,\dots,n}\) are equally likely, so \[ \mathsf{P}I_i=\mathsf{P}\set{\Pi(i)=i}=\frac{1}{n}. \] By linearity, \[ \mathsf{P}F_n=\sum_{i=1}^n \mathsf{P}I_i=\sum_{i=1}^n \frac{1}{n}=1. \] So the expected number of fixed points is \(1\), for every \(n\).

(One also gets \(\mathrm{Var}(F_n)=1\) exactly, but the expectation argument above is the clean first punchline.)

The full distribution of fixed points and the Poisson(1) limit

There is an exact formula for the pmf of \(F_n\). For \(k=0,1,\dots,n\), \[ \mathsf{P}(F_n=k) =\binom{n}{k}\frac{D_{n-k}}{n!} =\frac{1}{k!}\sum_{j=0}^{n-k}\frac{(-1)^j}{j!}, \] where \(D_m\) is the number of derangements of \(m\) items: \[ D_m=m!\sum_{j=0}^{m}\frac{(-1)^j}{j!}. \]

As \(n\to\infty\), \(F_n\) converges in distribution to a Poisson random variable with mean \(1\): \[ F_n \Rightarrow \mathrm{Poisson}(1), \qquad \mathsf{P}(F_n=k)\to e^{-1}\frac{1}{k!}\ \text{for each fixed }k. \] The dependence on \(n\) is real but becomes tiny quickly. In fact, \[ \left|\mathsf{P}(F_n=k)-e^{-1}\frac{1}{k!}\right| \le \frac{1}{k! (n-k+1)!}. \]

Cycle decomposition, cycle types, and partitions of \(n\)

Every permutation decomposes uniquely into disjoint cycles. The cycle type of \(\pi\in S_n\) is the multiset of its cycle lengths. For example, \((12)(345)(6)(789)\) has cycle lengths \(2,3,1,3\), so its type is the partition \(3+3+2+1\) of \(9\).

This gives a bijection:

- cycle types in \(S_n\) (equivalently conjugacy classes),

- integer partitions of \(n\).

Therefore, the number of cycle types in \(S_n\) is the partition function \(p(n)\).

Useful facts about \(p(n)\):

generating function \[ \sum_{n\ge 0} p(n)x^n=\prod_{k\ge 1}\frac{1}{1-x^k}; \]

Hardy–Ramanujan asymptotic \[ p(n)\sim \frac{1}{4n\sqrt{3}}\exp!\left(\pi\sqrt{\frac{2n}{3}}\right). \]

If a cycle type has \(m_i\) cycles of length \(i\) (so \(\sum_i i m_i=n\)), then the number of permutations having that type is the conjugacy class size \[ \#\set{\pi\in S_n:\text{type }(m_i)} =\frac{n!}{\prod_i i^{m_i} m_i!}. \]

This is the formula that a “cycle-type table” computes row by row.

Transpositions and cycles

A related identity that often comes up: the minimal number of arbitrary transpositions needed to express \(\pi\) is \[ \ell(\pi)=n-c(\pi), \] where \(c(\pi)\) is the number of cycles of \(\pi\) (counting fixed points as 1-cycles). Hence for uniform \(\Pi\), \[ \mathsf{P}\,\ell(\Pi)=n-\mathsf{P}\,c(\Pi). \] A standard fact is \(\mathsf{P}\,c(\Pi)=H_n=\sum_{k=1}^n \frac{1}{k}\), giving \[ \mathsf{P},\ell(\Pi)=n-H_n. \] See Section 1.6 for a sketch proof.

The 100 prisoners (locker) problem and why cycles control it

Problem (standard version):

- There are \(N\) prisoners labeled \(1,\dots,N\).

- There are \(N\) labeled boxes, each containing exactly one prisoner label, arranged as a uniformly random permutation.

- Prisoners enter one at a time. Each may open at most \(N/2\) boxes.

- No communication occurs during the process.

- The group survives iff every prisoner finds their own label among the boxes they open.

Cycle-following strategy:

Prisoner \(i\) opens box \(i\). If it contains \(i\), stop. Otherwise it contains some \(j\), and the prisoner next opens box \(j\), and continues in this way, for at most \(N/2\) opens.

Why this is cycle decomposition:

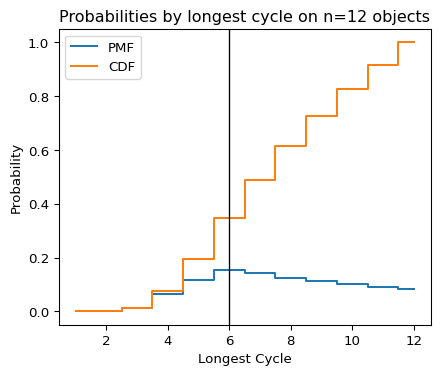

Let \(p\) be the permutation “box label \(\mapsto\) label inside the box”. The prisoner’s sequence of opened boxes is \[ i,\ p(i),\ p^2(i),\dots \] which stays within the cycle of \(i\) in the disjoint-cycle decomposition of \(p\). Prisoner \(i\) succeeds within \(N/2\) opens iff the cycle containing \(i\) has length at most \(N/2\). Therefore, everyone succeeds iff the permutation has no cycle longer than \(N/2\).

Success probability:

Write \(N=2n\). Then the success probability under the cycle-following strategy is \[ \mathsf{P}(\text{success}) =1-\sum_{k=n+1}^{2n}\frac{1}{k} =1-(H_{2n}-H_n). \] For \(N=100\) (\(n=50\)), \[ \mathsf{P}(\text{success})=1-(H_{100}-H_{50})\approx 0.311827. \] As \(n\to\infty\), \[ H_{2n}-H_n\to \ln 2, \qquad \mathsf{P}(\text{success})\to 1-\ln 2\approx 0.306853. \]

That number is the headline: the strategy turns a seemingly hopeless situation into about a 31% chance of total success, and the reason is entirely “no cycle longer than half.”

| Fixed Points | Probability | Poisson | Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.36788 | 0.36788 | 0.0% |

| 1 | 0.36788 | 0.36788 | -0.0% |

| 2 | 0.18394 | 0.18394 | 0.0% |

| 3 | 0.06131 | 0.06131 | -0.0% |

| 4 | 0.01533 | 0.01533 | 0.0% |

| 5 | 0.00307 | 0.00307 | -0.0% |

| 6 | 511.188u | 510.944u | 0.0% |

| 7 | 72.751u | 72.992u | -0.3% |

| 8 | 9.301u | 9.124u | 1.9% |

| 9 | 918.577n | 1.014u | -9.4% |

| 10 | 137.787n | 101.378n | 35.9% |

| 12 | 2.088n | 768.013p | 171.8% |

Claim

Let \(c(\Pi)\) be the number of cycles in the disjoint-cycle decomposition of \(\Pi\). Then \[ \mathsf{P}\,c(\Pi)=H_n=\sum_{k=1}^n \frac{1}{k}. \]

Proof sketch via “insert \(n\)” recursion

Let \(\Pi_n\) be uniform on \(S_n\), and write \(C_n:=c(\Pi_n)\).

1. Build a uniform permutation on \(n\) letters from one on \(n-1\) letters.

Start with \(\sigma\in S_{n-1}\). Write \(\sigma\) in disjoint cycles. There are \(n-1\) “slots” in total across all cycles if you think of writing each cycle in cyclic notation and allowing insertion immediately after any element. Choose one of these \(n-1\) slots uniformly and insert \(n\) there. This produces a permutation \(\tilde\sigma\in S_n\).

Also allow one extra possibility: make \(n\) a new 1-cycle \((n)\).

So there are \(n\) equally likely ways to place \(n\):

- with probability \(1/n\), start a new cycle \((n)\),

- with probability \((n-1)/n\), insert \(n\) into an existing cycle (in one of the \(n-1\) slots).

One can check (standard) that if \(\sigma\) is uniform on \(S_{n-1}\) and the slot is chosen uniformly, the resulting \(\tilde\sigma\) is uniform on \(S_n\).

2. Track how the number of cycles changes.

- If \(n\) becomes its own cycle, then \(C_n=C_{n-1}+1\).

- If \(n\) is inserted into an existing cycle, then you do not change the number of cycles: \(C_n=C_{n-1}\).

Therefore \[ C_n = C_{n-1} + I_n, \] where \(I_n\) is the indicator of the event “\(n\) starts a new cycle”, and \[ \mathsf{P}I_n=\frac{1}{n}. \]

3. Take expectations.

By linearity, \[ \mathsf{P}C_n = \mathsf{P}C_{n-1} + \mathsf{P}I_n = \mathsf{P}C_{n-1} + \frac{1}{n}. \] With base case \(C_1=1\), iterating gives \[ \mathsf{P}C_n = 1 + \sum_{k=2}^n \frac{1}{k} = \sum_{k=1}^n \frac{1}{k}=H_n. \]