12. General Botany

Vascular Plants

A vascular plant has specialized tissues, known as vascular tissues, for transporting water, nutrients, and sugars throughout the plant. These tissues are essential for supporting the plant’s growth and allowing it to distribute the substances needed for survival.

The two main types of vascular tissues are:

- Xylem: Transports water and dissolved minerals from the roots to the rest of the plant.

- Phloem: Transports sugars and other organic nutrients, which are produced through photosynthesis, from the leaves to other parts of the plant.

Vascular plants, also called tracheophytes, include all flowering plants (angiosperms), conifers (gymnosperms), ferns, and others. They are distinguished from non-vascular plants, such as mosses and liverworts, which do not have these specialized transport tissues and rely on simpler methods like diffusion to move water and nutrients.

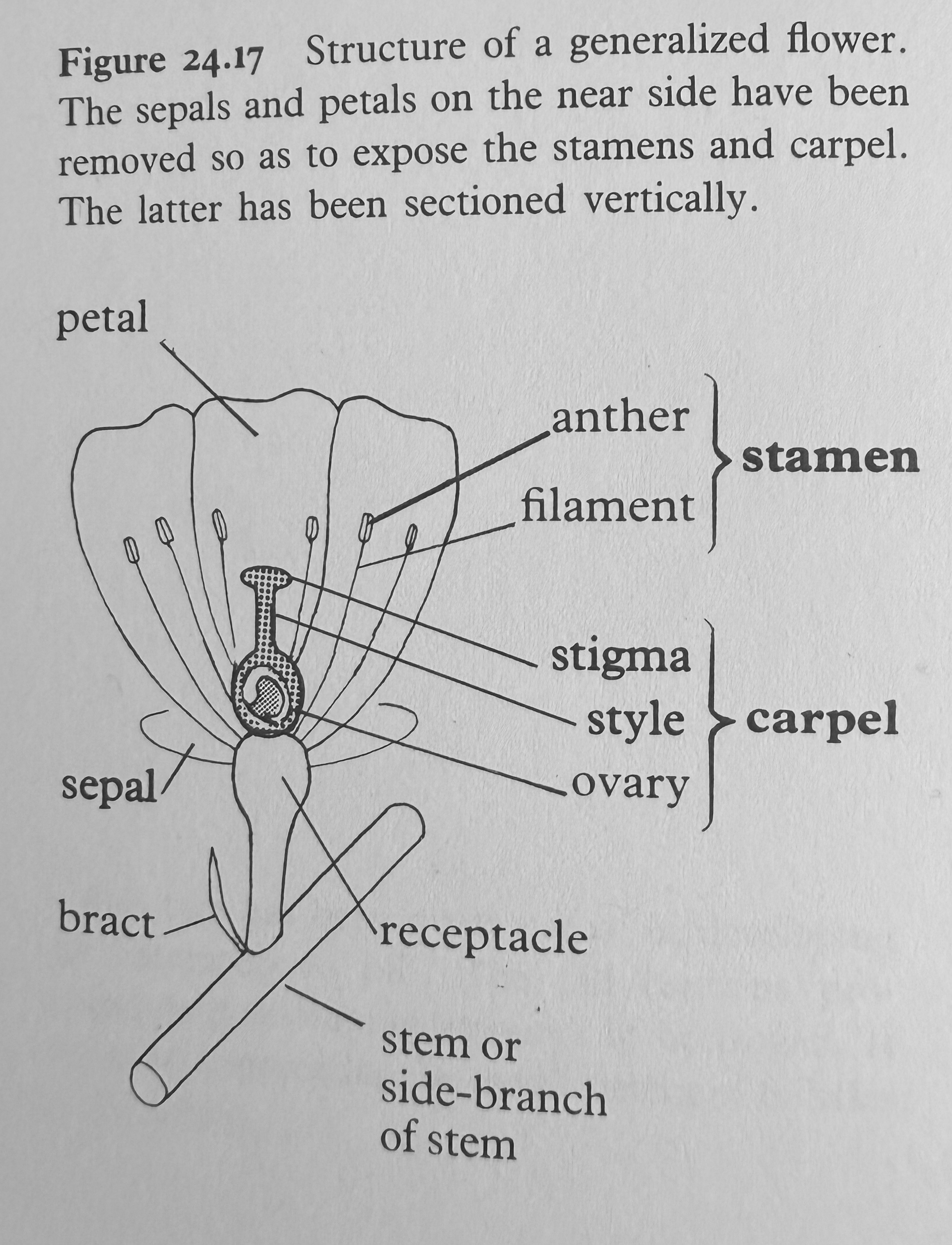

Parts of a Flower

The parts of a flower have names rooted in Latin and Greek, reflecting their shape, function, or appearance. The stigma comes from the Latin stigma, meaning “mark”, “puncture”, or “brand,” which in turn originates from the Greek stígma, referring to its role in marking the reproductive organ. The style derives from the Latin stylus, meaning “column” or “pillar,” which connects the stigma to the ovary. The ovary, from Latin ovarium (egg receptacle), refers to the structure that contains the ovules. The anther comes from Greek anthēros, meaning “flowery,” because it produces pollen. The filament is derived from Latin filamentum, meaning “thread,” referring to its thread-like appearance. The sepal comes from French sépale, based on the Greek skepē (covering), for its role in protecting the flower bud. The petal comes from Greek petalon, meaning “leaf,” describing the often colorful part that attracts pollinators. The carpel from the Greek word karpos meaning “fruit”, is the basic unit of the female part of the flower, consisting of the stigma, style, and ovary. The pistil, from Latin pistillum (pestle), refers to the female reproductive organ, is named for its shape. It can be made of a single carpel (simple pistil) or multiple fused carpels (compound pistil). The figure shows a simple pistil. Finally, the stamen, from Latin stamen (thread or warp in weaving fro Proto-Indo-European stɑ̄ “to stand”), describes the male reproductive organ, composed of the anther and filament, referencing its standing, thread-like structure. These etymologies link the physical characteristics of the flower parts to their ancient linguistic roots.

All flowers can be perfect (bisexual) like cherry and apple, monoecious with both male and female flowers on one tree, like oak, hazel, and birch, or dioecious, meaning they have distinct male and female individuals, and only the female trees produce fruit or seeds. In dioecious species, the male trees produce pollen, while the female trees bear the fruit or seeds.

Gymnosperm Tree Sex

Conifers reproduce through cones instead of flowers. Conifers have two main types of cones that serve reproductive functions: male cones (pollen cones) and female cones (seed cones). Male cones are small and soft, producing pollen that is dispersed by the wind. Female cones are typically larger and woody, containing ovules that, once fertilized by pollen, develop into seeds. This is similar to the male stamens and female carpels of flowers.

Conifers, like flowering plants, can be either monoecious or dioecious. Monoecious conifers, such as pines, spruces, and firs, have both male and female cones on the same tree, allowing for pollination within the same plant. On the other hand, dioecious conifers, such as yew and juniper, have separate male and female trees. In these species, male trees produce only pollen cones, while female trees produce only seed cones.

While conifers lack flowers, their reproductive structures perform the same basic roles: pollen (from male cones) fertilizes ovules (in female cones), leading to seed production. This division of male and female reproductive functions in cones mirrors the sex differentiation seen in flowering plants, even though the mechanisms for pollination (typically wind in conifers) are different.

In conifers, all cones are unisexual, meaning each cone is either male or female but never both. Unlike some flowering plants that can have perfect flowers (containing both male and female parts), conifers do not have cones that combine both male and female reproductive organs.

Fruit or Not?

The female ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba) does produce something that looks and smells like fruit. However, botanically speaking, this structure is not considered a “fruit” (ginkgos are gymnosperms, and by definition, gymnosperms do not produce true fruit). Here’s why it doesn’t count as a fruit:

Gymnosperm Seeds: Ginkgos, as gymnosperms, produce “naked seeds.” This means their seeds are not enclosed in an ovary (which is a defining feature of fruit). In angiosperms (flowering plants), seeds develop inside an ovary, which matures into a fruit that encloses the seeds.

Ginkgo Seeds: The fleshy, outer layer that surrounds ginkgo seeds is called a sarcotesta, and it resembles the outer part of a fruit. However, because it does not come from an ovary, it is not classified as a true fruit. This structure serves to protect and disperse the seeds, much like fruit does in angiosperms, but it forms differently.

In summary, while the fleshy ginkgo seeds look and behave like fruit in many ways (including having an unpleasant smell when they fall), they are technically not fruit because they are produced by a gymnosperm, which lacks flowers and ovaries.

The difference between yew “berries” and holly berries lies in the distinction between gymnosperms and angiosperms, and how fruits are defined botanically. Holly (Ilex spp.) is an angiosperm, meaning it belongs to the group of flowering plants. In angiosperms, seeds are enclosed within an ovary, which later develops into a fruit after fertilization. Holly berries are true fruits because they develop from the ovary of a flower, enclosing seeds inside their fleshy tissue. These red berries are examples of drupes, a type of fleshy fruit with a hard seed inside, and they come from the reproductive process typical of flowering plants.

Yew (Taxus spp.), on the other hand, is a gymnosperm, a non-flowering plant that does not produce true fruits. Gymnosperms do not have ovaries, and their seeds are considered “naked,” meaning they are not enclosed in a fruit. What looks like a berry on a yew tree is actually a fleshy structure called an aril, which forms around the seed. Since this structure is not derived from an ovary, it does not qualify as a true fruit. The aril is a fleshy red covering that surrounds the seed, but the seed itself remains exposed, a typical feature of gymnosperms. Therefore, holly berries are true fruits, while yew “berries” are arils and not considered fruits in the botanical sense.

Types of Seeds

A seed is a plant’s reproductive structure formed from a fertilized ovule after pollination. It contains an embryo, which will grow into a new plant, nutritive tissue (either endosperm in monocots or cotyledons in dicots) to support the embryo’s growth, and a protective seed coat. Seeds allow plants to reproduce, providing the embryo with food and protection during dormancy, and enabling it to germinate when conditions are favorable. They can remain dormant for long periods, making seeds crucial for plant survival and dispersal.

- Angiosperm Seeds

- Seeds produced by flowering plants, enclosed within a fruit. Examples: Apple seeds, walnut seeds, pea seeds.

- Gymnosperm Seeds

- Naked seeds not enclosed in a fruit, found exposed on cones or other structures. Examples: Pine seeds, spruce seeds, cycad seeds.

- Dehiscent Seeds

- Seeds released from their fruit or pod when it splits open naturally. Examples: Peas, beans, poppies.

- Indehiscent Seeds

- Seeds that remain inside the fruit or pod, which does not split open. Examples: Acorns, sunflower seeds, maple seeds.

- Monocot Seeds

- Seeds of monocotyledon plants, having one embryonic leaf and typically containing endosperm. Examples: Corn, rice, wheat.

- Dicot Seeds

- Seeds of dicotyledon plants, having two embryonic leaves, with nutrients often stored in the cotyledons. Examples: Bean seeds, sunflower seeds, oak seeds.

- Recalcitrant Seeds

- Seeds that do not survive drying or freezing, requiring moisture to remain viable. Examples: Chestnut seeds, avocado seeds, mango seeds.

- Orthodox Seeds

- Seeds that can be dried and stored for long periods, often used in seed banks. Examples: Wheat seeds, rice seeds, most crop seeds.

- Epigeal Germination Seeds

- Seeds whose cotyledons emerge above ground during germination. Examples: Bean seeds, pumpkin seeds.

- Hypogeal Germination Seeds

- Seeds whose cotyledons remain below the soil during germination. Examples: Pea seeds, oak acorns.

- Nut

- A nut is a dry, indehiscent fruit, meaning it does not split open at maturity to release their seed. A true nut (like an acorn or chestnut) has a hard, tough shell that surrounds the seed. While in everyday language “fruit” often refers to soft, fleshy things like apples or berries, in botanical terms, nuts fall under the broader category of fruits.

Types of Fruit

A fruit is the mature ovary of a flower, typically containing seeds. Its primary function is to aid in seed dispersal. Fruits can be fleshy (like berries or drupes) or dry (like nuts or capsules). All seeds are enclosed within fruits, but the structure and texture of the fruit can vary widely.

Fruit vs. Nut:

A fruit is any structure derived from the ovary of a flower and containing seeds. This includes fleshy fruits (e.g., apples, berries) and dry fruits (e.g., legumes, nuts, capsules). A nut is a type of dry, hard-shelled fruit where the seed remains inside the hard shell, and the fruit does not open naturally to release the seed. Nuts develop from a single ovary, are usually one-seeded, and the shell is hard and thick (e.g., acorns, chestnuts).

Categories of Fruit:

- Fleshy Fruits:

- Berry: Entire fruit is fleshy with multiple seeds (e.g., tomato, grape).

- Drupe: A fleshy fruit with a single hard stone (pit) enclosing the seed (e.g., peach, cherry).

- Pome: A fruit with a fleshy outer layer and a core containing seeds (e.g., apple, pear).

- Dry Fruits:

- Nut: Hard, indehiscent (does not split open), with a single seed inside a tough shell (e.g., acorn, chestnut).

- Capsule: A dry fruit that splits open to release seeds when mature (e.g., poppy, horse chestnut).

- Legume: A dry fruit that splits along two sides, characteristic of the pea family (e.g., peas, beans).

- Samara: A winged dry fruit aiding wind dispersal (e.g., maple, ash).

- Achene: A small, dry fruit with a single seed that is not fused to the fruit wall (e.g., sunflower seeds, sycamore).

- Compound Fruits:

- Aggregate Fruit: Formed from multiple ovaries of a single flower (e.g., raspberry, blackberry).

- Multiple Fruit: Formed from the ovaries of multiple flowers that fuse together (e.g., pineapple, fig).

Examples of Fruit

| Type | Description | Tree Examples (Common & Latin Name) | Supermarket Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drupe | A fleshy fruit with a single seed enclosed in a hard endocarp (pit). | Walnut (Juglans regia), Cherry (Prunus avium) | Peaches, Plums, Cherries |

| Capsule | A dry fruit that splits open when mature to release seeds. | Sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua), Eucalyptus (Eucalyptus globulus) | None commonly found |

| Achene | A small, dry fruit with a single seed not attached to the fruit wall. | Sycamore (Acer pseudoplatanus), Linden (Tilia cordata) | Sunflower seeds |

| Samara | A winged achene (dry fruit with a single seed) that aids in wind dispersal. | Ash (Fraxinus excelsior), Elm (Ulmus minor) | None commonly found |

| Nut | A dry, hard-shelled fruit that does not open to release the seed. | Oak (Quercus robur), Chestnut (Castanea sativa) | Hazelnuts, Chestnuts |

| Berry | A fleshy fruit with multiple seeds embedded in the pulp. | Elderberry (Sambucus nigra), Holly (Ilex aquifolium) | Grapes, Blueberries, Tomatoes |

| Pome | A fleshy fruit with a core containing seeds. | Apple (Malus domestica), Pear (Pyrus communis) | Apples, Pears |

| Legume | A dry fruit that splits along two sides to release seeds. | Black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia), Acacia (Acacia spp.) | Peas, Green Beans |

| Aggregate Fruit | A fruit formed from multiple ovaries of a single flower. | Magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora) | Raspberries, Blackberries |

| Multiple Fruit | A fruit formed from the fusion of several flowers. | Fig (Ficus carica), Mulberry (Morus alba) | Pineapple, Fig |

| Cone | Woody fruit with scales containing seeds. | Pine (Pinus sylvestris), Cypress (Cupressus sempervirens) | None commonly found |

Radiation and Speciation

Speciation refers to the process by which a single species splits into two or more distinct species. This occurs when populations of a species become reproductively isolated (due to geographic, behavioral, genetic, or ecological factors) and undergo evolutionary changes that prevent them from interbreeding in the future. Speciation is the fundamental process driving the formation of new species over time.

Radiation, particularly adaptive radiation, refers to the rapid diversification of a single ancestral species into multiple new species, typically in response to new ecological opportunities or environments. During radiation, many new species evolve to occupy different ecological niches, often in a relatively short period of time. A famous example is Darwin’s finches in the Galápagos Islands, where a single ancestral species gave rise to multiple species, each adapted to different food sources and habitats.

Chromosomes

| Genus | Species | Common Name | Chromosome Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acer | Acer platanoides | Norway Maple | Diploid (2n = 26) |

| Alnus | Alnus glutinosa | Common Alder | Diploid (2n = 28) |

| Betula | Betula pendula | Silver Birch | Diploid (2n = 28) |

| Cinnamomum | Cinnamomum camphora | Camphor Tree | Diploid (2n = 24) |

| Corylus | Corylus avellana | Common Hazel | Diploid (2n = 28) |

| Crataegus | Crataegus monogyna | Hawthorn | Diploid (2n = 34) |

| Fagus | Fagus sylvatica | European Beech | Diploid (2n = 24) |

| Fraxinus | Fraxinus excelsior | European Ash | Diploid (2n = 46) |

| Ilex | Ilex aquifolium | English Holly | Diploid (2n = 40) |

| Juglans | Juglans regia | English Walnut | Diploid (2n = 32) |

| Liriodendron | Liriodendron tulipifera | Tulip Tree | Diploid (2n = 38) |

| Magnolia | Magnolia grandiflora | Southern Magnolia | Diploid (2n = 38) |

| Malus | Malus domestica | Apple | Diploid (2n = 34) |

| Morus | Morus alba | White Mulberry | Diploid (2n = 28) |

| Myristica | Myristica fragrans | Nutmeg | Diploid (2n = 40) |

| Persea | Persea americana | Avocado | Diploid (2n = 24) |

| Populus | Populus tremula | European Aspen | Diploid (2n = 38) |

| Prunus | Prunus avium | Sweet Cherry | Diploid (2n = 16) |

| Pterocarya | Pterocarya fraxinifolia | Caucasian Wingnut | Diploid (2n = 32) |

| Quercus | Quercus robur | English Oak | Diploid (2n = 24) |

| Robinia | Robinia pseudoacacia | Black Locust | Diploid (2n = 20) |

| Tilia | Tilia cordata | Small-leaved Lime | Diploid (2n = 82) |

| Ulmus | Ulmus glabra | Wych Elm | Diploid (2n = 28) |

| Rosa | Rosa canina | Dog Rose | Polyploid (2n = 35-42) |

| Acer | Acer pseudoplatanus | Sycamore Maple | Tetraploid (4n = 52) |

| Betula | Betula pubescens | Downy Birch | Tetraploid (4n = 56) |

| Populus | Populus tremula | Aspen | Tetraploid (4n = 76) |

| Quercus | Quercus petraea | Sessile Oak | Tetraploid (4n = 48) |

| Sorbus | Sorbus aucuparia | Rowan | Tetraploid (2n = 68) |

| Crataegus | Crataegus laevigata | Midland Hawthorn | Hexaploid (6n = 102) |

| Fraxinus | Fraxinus angustifolia | Narrow-leaved Ash | Hexaploid (6n = 138) |