Climate and Climate Change VSIs

Climate and Climate Change

Climate Change VSI was originally published as Global Warming.

Climate

- p48: HU energy release 50 to 200 exajoules (\(10^{18}\)) per day or about 1 petawatt

- p60/Ch 5: climates in worlds with different land mass arrangement

- p80: Antarctica ice melts = 65m increase in sea level

- p87: orbital forcing, last 2.5m years and ice ages

- p106: weather change and civilization collapse — 4200 years ago a cold arid event

- p127: 8.5Gt carbon per year released

GPT on weather change and civilization collapse

The 4.2-kiloyear event, occurring around 2200 BCE, was a significant climate event that led to widespread droughts and is thought to have influenced the collapse of several ancient civilizations. In Egypt, exceptionally low Nile floods around 2150 BCE may have contributed to the collapse of the Old Kingdom. In the Middle East, particularly in Mesopotamia, enhanced dust flux and intense aridity were recorded, which might have played a role in the collapse of the Akkadian Empire. There are archaeological signs of widespread abandonment in northern Mesopotamia and a dramatic influx of refugees into southern Mesopotamia around 2170 BCE. In the Indus Valley region, there’s evidence of recurring droughts affecting the Indus Civilization, leading to changes in settlement patterns and agriculture Nature.

The Akkadian Empire, one of the affected civilizations, faced a centuries-long drought that is believed to have caused widespread agricultural failures and societal upheaval. Similarly, in the Indus Valley, the drought is associated with significant societal transformations, including the abandonment of major cities and changes in agricultural practices. These events demonstrate the profound impact that climate change and environmental factors can have on civilizations, underscoring the interconnectedness of human societies and their environments.

Climate Change

- p51: SSP descriptions

- p87: Finland once had malaria

- p95: East and West Antarctica ice sheets are very different

- p101: Subsurface temperature gradient is 30 degrees C per km

- p109: 2009 Copenhagen climate meeting a fiasco, Obama, Snowden

- p126: GDP growth and carbon use decoupling

- p134: 50% of air pollution from cars comes from tires, brake pads, and road surface wear

- p136: huge fossil fuel subsidies and wide public ownership of large oil companies (outside US)

- p139: reforestation in China

Climate Change Summary from p43

The IPCC 2021 report states that the evidence for climate change is unequivocal, and there is very high confidence that this warming is due to human emissions of GHGs. This statement is supported by six main lines of evidence:

the rise in GHGs in the atmosphere has been measured and the isotopic composition of the gases shows that the majority of the additional carbon comes from the burning of fossil fuels;

laboratory and atmospheric measurements show that these gases absorb heat;

significant changes in global temperatures and sea-level rise have been observed over the past century;

other significant changes have been observed in the cryosphere, oceans, land, and atmosphere including retreating ice sheets, sea ice, and glaciers, and extreme weather events, all of which can be directly attributed to the impact of climate change;

there is clear evidence that natural processes including sunspots and volcanic eruptions cannot explain the warming trend over the past 100 years; and

we now have a deeper understanding of the longer term climate changes of the past and the critical role GHGs have played in regulating the climate of our planet.

Denier’s Positions

- Ice core data shows CO2 lags temperature not leads it (see Shakun below)

- CO2 small part of atmosphere and therefore can’t have a large impact

- Data is tweaked

- It’s all sun spot activity

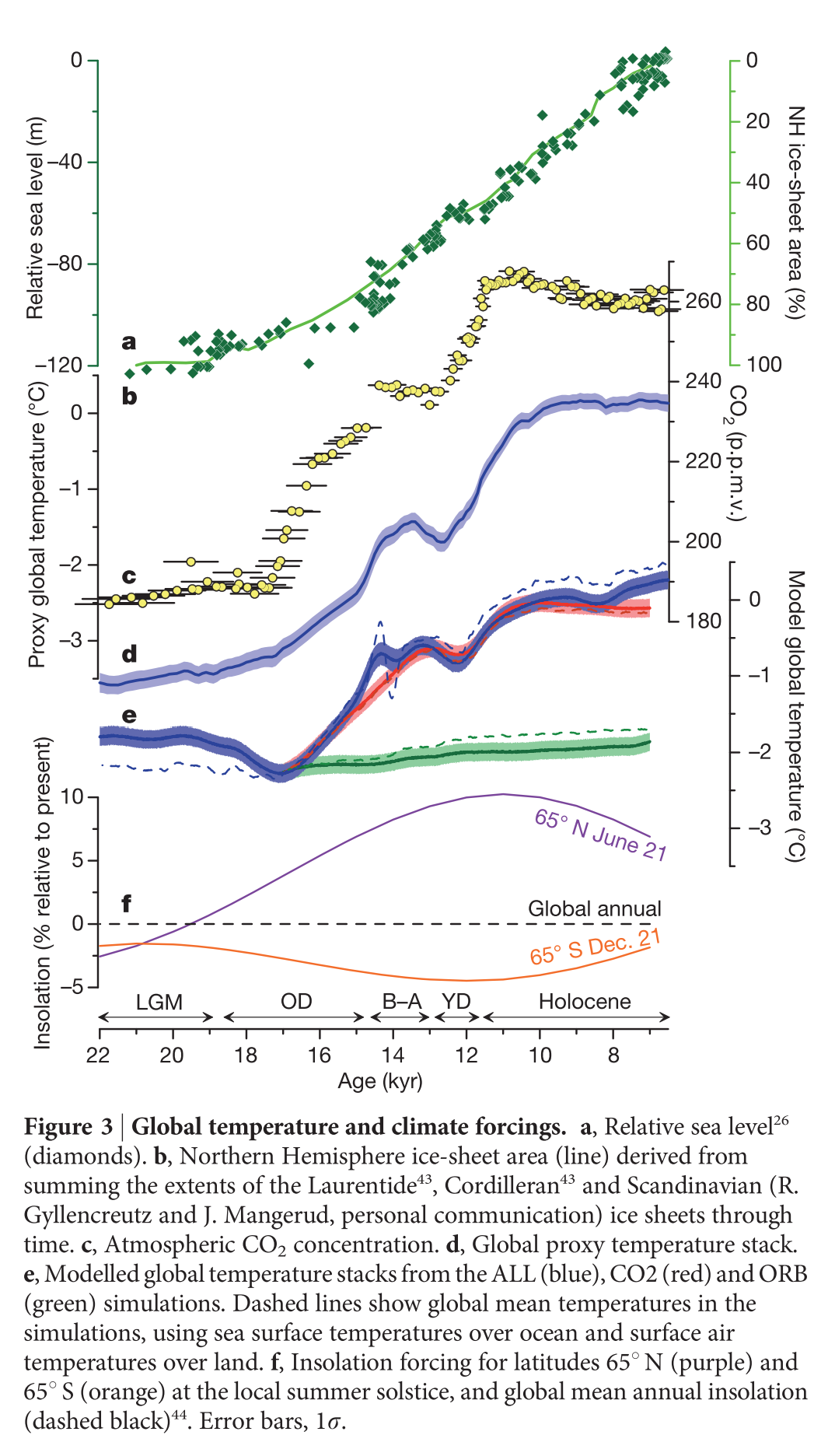

Ice Age Temperature and CO2

GPT

The relationship between CO2 levels and temperature during ice ages has been a subject of extensive study, especially through the analysis of ice core data. The general consensus is that changes in Earth’s orbit, known as Milankovitch cycles, initiate the end of ice ages, leading to a warming effect. This initial warming causes CO2 levels to rise, which then amplifies the warming through a positive feedback mechanism.

Specifically, studies of ice cores show that there is a lag of about 800 years between initial temperature increases and subsequent rises in CO2 levels. After this initial phase, temperature and CO2 concentrations rise together for thousands of years. The suggestion is that orbital changes likely trigger a temperature increase, which then causes CO2 levels to rise, further warming the planet. This interaction between CO2 and temperature is seen as a feedback loop that amplifies initial warming triggered by changes in Earth’s orbit ref1, ref2.

Moreover, scientific discussions highlight that while CO2 and temperature show a strong correlation over the past half million years, the relationship is complex and influenced by various factors, including oceanic processes and biological activity. For example, CO2 is less soluble in warmer water, which can lead to increased atmospheric CO2 as the oceans warm. Additionally, changes in biological activity in the oceans can also affect CO2 levels.

In summary, while CO2 levels do initially lag behind temperature increases at the end of ice ages, they play a crucial role in amplifying the warming initiated by changes in Earth’s orbit. The interplay between CO2 and temperature is a critical aspect of understanding past climate changes and provides insights into the potential impacts of current increases in greenhouse gases ref ref.

Claude

The relationship between CO2 levels and temperature changes during the ice ages has been a topic of significant research and debate. The available evidence suggests that CO2 changes generally lagged behind temperature changes, but there is also evidence of a complex interplay between the two. Here’s a detailed explanation:

Ice core records: Ice cores from Antarctica, such as the Vostok ice core, provide a record of past CO2 levels and temperature changes over the past 800,000 years. These records show that CO2 levels and temperature are closely correlated, with lower CO2 levels during cold glacial periods and higher levels during warm interglacial periods (Petit et al., 1999).

Lag between temperature and CO2: Analysis of the ice core data reveals that temperature changes typically preceded changes in CO2 levels by several hundred to a few thousand years (Caillon et al., 2003; Shakun et al., 2012). This suggests that initial temperature changes were driven by factors other than CO2, such as changes in Earth’s orbit (Milankovitch cycles) or variations in solar activity.

Feedback mechanisms: Although CO2 changes lagged behind initial temperature changes, the increasing CO2 levels likely acted as a positive feedback, amplifying the warming trend. As the Earth warmed, more CO2 was released from the oceans and land, leading to further warming (Shakun et al., 2012). This feedback mechanism is known as the “CO2 feedback” and is thought to have played a significant role in the transition from glacial to interglacial periods.

Leads and lags: While the general pattern shows CO2 lagging behind temperature, there is evidence of more complex interactions. A study by Parrenin et al. (2013) suggests that during the last deglaciation (around 18,000 to 11,000 years ago), CO2 may have led temperature changes in Antarctica by 800 ± 600 years. This highlights the potential for regional variations and the complexity of the climate system.

Current anthropogenic CO2 increase: It is important to note that the current rapid increase in atmospheric CO2 levels is primarily driven by human activities, such as burning fossil fuels and deforestation. This is distinct from the natural CO2 changes observed during the ice ages and is causing global warming at an unprecedented rate (IPCC, 2021).

In summary, the evidence from ice core records suggests that during the ice ages, CO2 changes generally lagged behind temperature changes, with temperature initially driven by other factors. However, the increasing CO2 levels likely acted as a positive feedback, amplifying the warming trend. The relationship between CO2 and temperature is complex, with evidence of regional variations and potential leads and lags. The current anthropogenic increase in CO2 is a separate issue, driving rapid global warming.

References:

- Caillon, N., et al. (2003). Timing of atmospheric CO2 and Antarctic temperature changes across Termination III. Science, 299(5613), 1728-1731.

- IPCC (2021). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- Parrenin, F., et al. (2013). Synchronous change of atmospheric CO2 and Antarctic temperature during the last deglacial warming. Science, 339(6123), 1060-1063.

- Petit, J. R., et al. (1999). Climate and atmospheric history of the past 420,000 years from the Vostok ice core, Antarctica. Nature, 399(6735), 429-436.

- Shakun, J. D., et al. (2012). Global warming preceded by increasing carbon dioxide concentrations during the last deglaciation. Nature, 484(7392), 49-54. link

Shakun has 1400 citations. Abstract:

The covariation of carbon dioxide (CO2) concentration and temperature in Antarctic ice-core records suggests a close link between CO2 and climate during the Pleistocene ice ages. The role and relative importance ofCO2 in producing these climate changes remains unclear, however, in part because the ice-core deuterium record reflects local rather than global temperature. Here we construct a record of global surface temperature from 80 proxy records and show that temperature is correlated with and generally lags CO2 during the last (that is, the most recent) deglaciation. Differences between the respective temperature changes of the Northern Hemisphere and Southern Hemisphere parallel variations in the strength of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation recorded in marine sediments. These observations, together with transient global climate model simulations, support the conclusion that an antiphased hemispheric temperature response to ocean circulation changes superimposed on globally in-phase warming driven by increasing CO2 concentrations is an explanation for much of the temperature change at the end of the most recent ice age.

Cooling between 1950 and 1980

Evidence supporting five explanations for the cooling trend observed from about 1950 to 1980:

Aerosol Emissions: Industrial activities, particularly in developed nations, emitted large quantities of aerosols, including sulfates. Studies show these aerosols can have a cooling effect by reflecting sunlight back into space and by acting as cloud condensation nuclei, increasing cloud reflectivity. Measurements of aerosol concentrations and their radiative properties provide evidence for their cooling effect during this period.

Volcanic Activity: Volcanic eruptions eject sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere, where it converts to sulfate aerosols. These aerosols reflect sunlight, cooling the Earth’s surface. Major eruptions, such as that of Mount Agung in 1963, El Chichón in 1982, and Mount Pinatubo in 1991, are known to have had significant cooling effects on the global climate. Ice core records, showing increased sulfate deposition during this period, provide evidence of enhanced volcanic activity.

Solar Variability: The solar output is not constant and undergoes various cycles, including the 11-year sunspot cycle. Periods of low solar activity, such as the Dalton Minimum, have been associated with cooler temperatures. Solar irradiance data, sunspot numbers, and cosmogenic isotope records (like carbon-14 and beryllium-10) in tree rings and ice cores serve as evidence for changes in solar activity during the mid-20th century.

Oceanic Cycles: Oceans can store and release heat over long periods, influencing global climate. The Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) and the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO) are examples of such cycles. Sea surface temperature records, along with climate models, indicate that these oscillations were in phases that could have contributed to a cooling trend during this period.

Data Quality and Coverage: Earlier global temperature records had less geographic coverage and lower quality compared to modern datasets. Many regions, especially in the Southern Hemisphere and the Arctic, were underrepresented. Improvements in data quality and analysis techniques have since provided a more accurate picture of global temperatures, indicating that the cooling might not have been as pronounced as initially thought when considering global averages.

Each of these factors contributed to the complexity of the climate system and influenced global temperatures, demonstrating the multi-faceted nature of climate change drivers beyond just greenhouse gas concentrations.

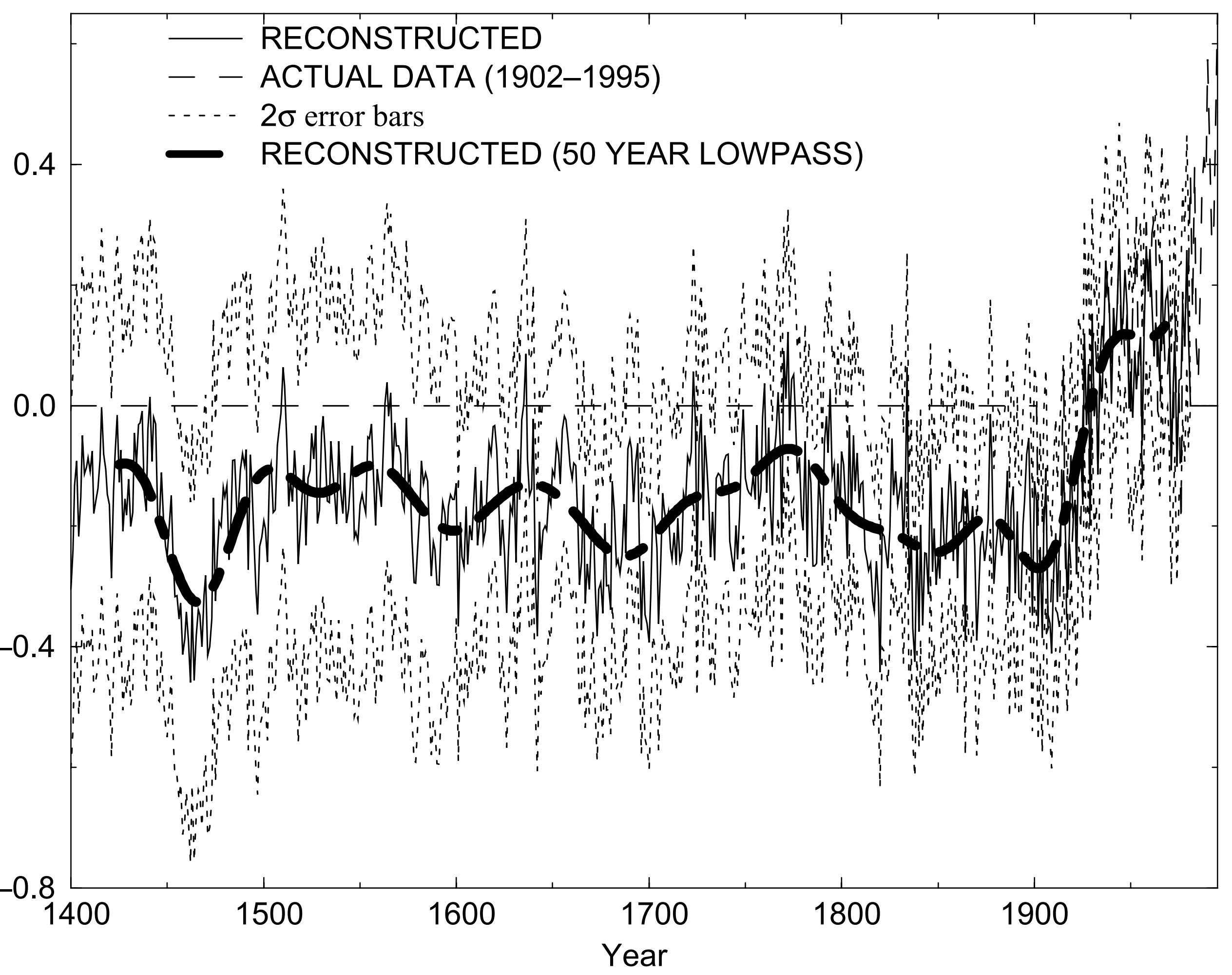

Hockey Stick Graph

Paper, currently with 2863 citations.

Publication of the Hockey Stick Graph

The hockey stick graph was first published in 1999 by climatologists Michael Mann, Raymond Bradley, and Malcolm Hughes. Their study, which appeared in the journal “Nature,”1 used tree-ring data and other proxies to reconstruct past climate temperatures, illustrating a significant rise in the 20th century after a long period of relatively stable temperatures.

Controversy

The graph sparked controversy for several reasons:

- Methodology: Critics questioned the statistical methods used to create the graph, arguing that they were flawed or biased.

- Data Interpretation: There were concerns about the interpretation of proxy data and its representation of past climate conditions.

- Political Implications: The graph became a focal point in climate change debates, with some suggesting it was used to exaggerate the impact of human activities on climate change.

Belief and Acceptance in the Scientific Community

Despite the controversy, the broad scientific consensus supports the notion of recent, unusual warming, as depicted by the hockey stick graph. Many subsequent studies, using various methods and data sources, have confirmed a sharp rise in global temperatures in the 20th and 21st centuries, aligning with the graph’s general trend.

Skeptics’ Views

Skeptics of the hockey stick graph argue on several fronts:

- Statistical Analysis: Some contend that the statistical methods used in the original study were improper or insufficiently robust, potentially skewing the results.

- Historical Context: Skeptics often point to past climate events, like the Medieval Warm Period, arguing that the graph understates these historical climate variations and thus the current warming trend is not unprecedented.

- Data Selection: There is criticism over the selection and handling of proxy data, with some suggesting that the data were cherry-picked or inadequately processed to produce a predetermined outcome.

Despite these criticisms, the fundamental concept of significant recent warming is widely supported in the climate science community, and the hockey stick graph remains a notable illustration in the discourse on climate change.

WSJ Article on Mann’s Case

This Scientist Fought His Attackers in Court—and Won

Michael Mann, the climatologist behind the infamous ‘hockey-stick graph,’ prevailed in a defamation case and says science is on a roll

PHILADELPHIA—Michael Mann is feeling pretty good about science.

The climate scientist, author of the “hockey-stick graph” paper that infamously depicted a shocking rise in postindustrial average temperatures, has been battling critics for more than two decades.

In that time, a state attorney general accused him of misusing public money. The National Research Council and the university that employed him investigated his research. And conservative commentators attacked his work and his character. There were death threats.

Then last month, Mann won a 12-year legal fight and a $1 million jury verdict against the conservative bloggers who called his work fraudulent and compared him to a pedophile. The defendants have said they would appeal.

Mann’s $1 million jury award comes when public trust in science is at a low, scientific journals are retracting more papers than ever before, and researchers in a range of disciplines are scrutinizing the work of their peers and calling out what they see as errors or shoddy work in public forums.

Despite these wobbles, Mann is optimistic about both the discoveries and the integrity of how science is conducted these days.

Mann won a $1 million jury verdict against conservative bloggers who called his work fraudulent.

“Science has given us remarkable advancements and achievements over the past decade,” Mann said in an interview in his office at the University of Pennsylvania where he is a professor of earth and environmental science. He cited gene-editing technology, the Covid-19 vaccine and space probes landing on asteroids. “Seems to me that science is actually on a winning streak,” he said.

What does Michael Mann’s court victory mean for climate scientists? Join the conversation below.

It is also true that some areas of science are under assault, he added. “Clearly that’s true with climate and is true in a different way with Covid-19. But, we don’t see public mistrust of the science of black holes, or the science of interstellar space travel.”

Mann said he feels vindicated by his court victory and hopes it will embolden other climate researchers to defend their work as vigorously as he has defended his own.

“I wasn’t going to shy away from fighting what I felt was the good fight,” said Mann, 58 years old. “A lot of scientists would have sort of shunned the spotlight, retreated and withdrawn. That wasn’t in my nature.”

Soft-spoken in person, Mann can be a tiger online. He spars with critics on his X account, where he has more than 220,000 followers. He punches back in frequent newspaper opinion pieces, letters to the editor, television interviews and on podcasts. In 2024 alone, he has done more than 20 interviews with major news outlets, from CNN to Le Monde. His public message is simple: The climate is changing rapidly, but it isn’t too late to save the planet.

Mann grew up in Amherst, Mass., the son of a math professor and a teacher. A self-described computer nerd in high school, he studied applied math and physics at the University of California, Berkeley, then continued his studies at Yale, where he earned a Ph.D. in geology and geophysics and became interested in using math and computers to simulate the Earth’s climate.

Mann has an eclectic collection of books, including his own, in his campus office. He entered the public spotlight in 1998 as a 33-year-old postdoctoral researcher at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, when he and two colleagues published a paper in the journal Nature that used tree rings, ice cores and other proxy records to create a global temperature record from the present back to 1400 A.D.

That paper included what became a lightning rod for climate-change skeptics: a chart depicting a long period, beginning in 1400, of relatively stable temperatures followed by a sharp bend upward in temperatures starting in the late 1800s through the present—like a hockey stick on its side with the blade turned up.

“I’ve sort of felt like the hockey stick actually sort of overshadowed much of what we thought was most interesting in that original article,” Mann said.

Mann was co-author of a paper and hockey stick-shaped graph that was an early depiction of the rise in postindustrial average temperatures. Photo: IPCC and Michael Mann/Penn State Perhaps because the paper was published on Earth Day in 1998—at that time, the hottest year on record—the media picked up Mann’s paper and its findings.

Mann remembers his first television appearance on CBS Nightly News after the paper was published, when he was asked several times whether the hockey stick proved that humans were causing climate warming. Mann wasn’t ready to make that statement, telling the correspondent instead that it was “strongly suggestive.”

The finding was amplified when the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change published an updated version of the graph in its 2001 report and found that global temperatures were the warmest in 2,000 years.

Critics who didn’t believe in climate change, or thought Mann exaggerated the science to prove his point, attacked him.

In 2004, two critics disputed statistics used in the paper. They also pointed out errors in the listing of data used in the study. Mann and his co-authors issued a correction that didn’t alter the results of the paper.

Over the next eight years, Mann and his colleagues were the target of investigations by Republican lawmakers on Capitol Hill, Virginia’s Republican attorney general and officials at Pennsylvania State University, where he was a faculty member from 2005 to 2022.

In 2006, Mann’s research was confirmed by the National Research Council after a request from Congress. In 2012, the Virginia Supreme Court rejected the claim by the state attorney general, Ken Cuccinelli, and the case was dismissed. The same year, Penn State cleared Mann of research misconduct after a four-month probe.

On his office wall is a certificate from the Nobel Prize committee acknowledging his contribution to the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize along with other scientists working with the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Attacks continued In 2012, Rand Simberg, an adjunct scholar at the Competitive Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank in Washington, D.C., compared Mann to Jerry Sandusky, the former Penn State football coach who was convicted of abusing young boys in the same year.

A separate article published a few months later by the National Review and written by conservative radio host and blogger Mark Steyn said, “Mann was the man behind the fraudulent climate-change ‘hockey-stick’ graph.”

Mann had had enough.

“It’s one thing to criticize our work,” he said. “It’s something else to make an actual accusation of fraud, which they did, and to compare me to a convicted child molester. I felt like I had to do something.”

He sued Simberg and Steyn for defamation in Washington, D.C., Superior Court.

Soft-spoken in person, Mann says he doesn’t shy away from a good fight. On Feb. 8, the jury awarded Mann $1 million in punitive damages from Steyn, $1,000 from Simberg and $1 in compensatory damages from each of them. Lawyers for Simberg and Steyn said they plan to appeal.

Simberg said he stands by his original blog post, and that he was critiquing Mann’s methods rather than the science of climate change.

“Science was on trial here, and I felt like I was the one defending it,” Simberg said.

Steyn’s attorney, H. Christopher Bartolomucci, said Steyn continues to believe the statements he made are true and not defamatory.

“We believe the $1 million punitive award is grossly excessive and unconstitutional in a case where Dr. Mann had only $1 in actual damages,” Bartolomucci said.

Mann’s critics, some of whom have appeared on the Opinion pages of The Wall Street Journal, have argued the case was about free speech and the right to criticize a public figure, something that Mann had become by the time Simberg and Steyn wrote their articles. Media organizations, including the Washington Post and the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, submitted friend-of-the-court filings on their behalf.

For now, Mann said he can return to his research—looking at how the jet stream may be affecting summer drought and heat waves as the result of climate warming.

As for the future of the planet, Mann said it isn’t too late to prevent the worst effects of climate change. “As long as the obstacles aren’t physical or technological, but political, one can remain stubbornly optimistic,” he said.

Write to Eric Niiler at eric.niiler@wsj.com

Deets

- Mark Maslin

- Volumes 358 and 118 (4th ediition)

- Published 2013 and 2021 (originally 2004)

Footnotes

Mann, Michael E., Raymond S. Bradley, and Malcolm K. Hughes. “Global-scale temperature patterns and climate forcing over the past six centuries.” Nature 392.6678 (1998): 779-787.↩︎